Key Takeaways

- Decentralised finance strives to replicate financial services that are traditionally offered by institutions and intermediaries, but within cryptocurrency platforms using open protocols and sets of collaborators.

- While DeFi has shown the opportunity of building a more efficient, composable, and accessible financial ecosystem, it has also introduced new forms of risks less understood by the financial industry.

- These risks, such as technology, centralisation and third-party dependencies originate from the design choices of developers when tooling their applications within certain blockchain systems.

- We believe that the possibility of cohesive operations across modular financial applications is a promising development capable of disrupting traditionally siloed financial infrastructure; however, it is unclear whether DeFi as it is currently structured will be this solution, or how these developments may progress beyond their current infant stages.

Overview

If you’ve followed crypto over the last 6-12 months, it’s likely you’ve come across the term “DeFi” in relation to various cryptoassets and online applications. DeFi is short for decentralised finance, a newer term in the cryptocurrency industry.

Decentralised finance strives to replicate financial services that are traditionally offered by institutions and intermediaries, but within cryptocurrency platforms using open protocols and sets of collaborators. The overarching goal, in alignment with the origins of cryptocurrency, is to provide an alternative to legacy financial infrastructure that is more accessible, transparent and reduces trust in centralised parties.

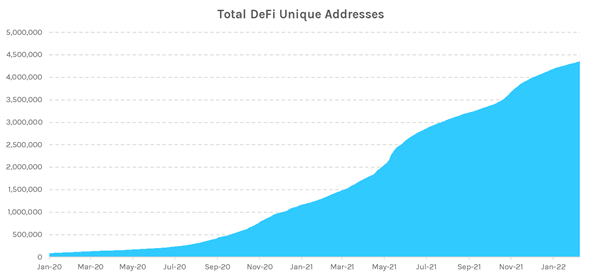

Source: Dune Analytics, CoinShares Research (February 2022)

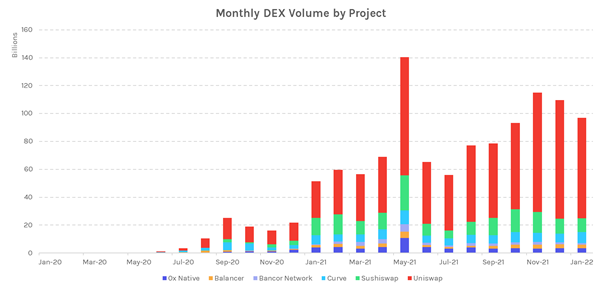

Source: Dune Analytics, CoinShares Research (February 2022)

Over the last couple of years, DeFi usage has exploded, with millions of users now accessing various products across several different platforms. The rapid development and adoption of DeFi products has therefore unsurprisingly caught the attention of users, investors, and regulators alike.

Background

As you probably know, Bitcoin was created to enable individuals to transact digital value directly with each other, without relying on any third party. Its birth enabled a different kind of financial system, based on a decentralized consensus, not on a centralized fiat currency.

While suitable to perform the functions of money, its base layer doesn’t offer the flexibility to perform more elaborate financial transactions that are commonplace in the real world such as access to credit markets, fixed income, or derivatives. This has raised a debate about how best to replicate these services while retaining the robust, decentralised, and trust minimised properties offered by Bitcoin.

Several solutions have been proposed: companies with bitcoin-native financial services such as Casa or Unchained Capital; supporting second-layer and side-chain technology such as Lightning or Liquid; and lastly alternative blockchains that make certain trade-offs against robustness, trust and decentralisation to enable increased functionalities, known broadly as ‘smart contracts’. These systems are therefore often referred to as smart contract platforms, prominent examples being Ethereum and Binance Smart Chain.

Today, DeFi predominantly relies on these smart contract platforms. DeFi projects are designed to perform any financial transaction that can be translated into computer code (or the smart contracts) without the added friction of institutions and intermediaries, and without the innovation-hampering limitations of regulation.

Examples of DeFi Products

As the DeFi ecosystem has grown, it’s become more and more of an umbrella term for projects that are attempting to solve different classes of problems.

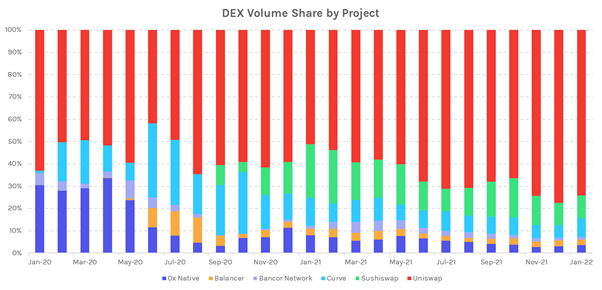

Source: Dune Analytics, CoinShares Research (February 2022)

Spot Exchange

Commonly referred to as Decentralised Exchanges (DEXs), these applications serve as automated marketplaces where peers can directly exchange between different assets. Their intended benefit is to mitigate the censorship, custody, accessibility, and trading pair issues that can arise from centralised exchanges.

Automated Market Makers (AMMs)

A core concept of the DEX landscape is a practice called automated market-making (AMM). Rather than the traditional order book style trading experience, where users’ ‘bid’ and ‘ask’ orders are matched for execution, the most prevalent DEXs offer pools of assets through which users can directly trade. In practice, anybody can provide liquidity by depositing assets to a pool—effectively the order book—and in return, depositors receive a tokenised claim that represents their redeemable share of the pool’s assets.

Examples: Uniswap, Balancer, Curve, SushiSwap, PancakeSwap, Bancor

Source: Dune Analytics, CoinShares Research (February 2022)

Order Book Exchanges

Order book exchanges have the most common look-and-feel to traditional trading venues, however, their infrastructure and mechanics vary considerably. Among one another, these DEXs are oftentimes distinguishable based on where they are hosted and how transactions are settled.

Order book exchanges established on-chain have proven to be challenging given the scalability conundrums of blockchain networks. Order books are also difficult to bootstrap. For these reasons, order-book exchanges are either hosted on blockchains that are specifically designed to support high-frequency activities, or they operate off-chain through third-party intermediaries that incrementally settle to an underlying blockchain. Notably, both tactics introduce forms of centralisation as a trade-off to scalability.

Examples: 0x, Serum

Lending and Borrowing

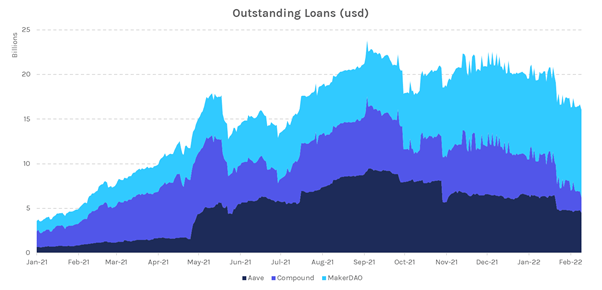

Mostly driven by speculative traders, DeFi credit markets allow users to lend or borrow crypto assets through automated processes that do not require personal information.

Given their structure, today’s DeFi loans may be better compared to financial instruments like swaps than to traditional commercial, consumer or mortgage loans. Through their over-collateralisation requirements, these protocols cannot fulfil the needs of those seeking to simply borrow money, yet they’re effective in making productive use of otherwise stagnant balance sheet assets.

Indeed, to provide protective assurances to a lender and create verifiable measures, two approaches have emerged:

- Credit can be secured with collateral, and oftentimes, projects require over-collateralisation, meaning users must post assets more than the value they seek to borrow.

- Credit can also be lent under the condition that it will be repaid immediately, meaning the borrower receives a loan, uses and repays it within the same on-chain transaction. This is called a flash loan, it’s undoubtedly novel, however, highly experimental and has led to several exploits in practice.

Collateralised Debt Positions

Collateralised debt positions (CDPs) are created when users lock assets and receive newly minted credit tokens in return. Essentially, these tokens represent secured loans that don’t require counterparty risk and enable users to receive a liquid asset while maintaining exposure to their pledged collateral. The process is carried out by a dedicated protocol and set of programs that escrow collateral until a debt is fully repaid or the value of collateral falls below a certain threshold.

While it may seem underwhelming, this system laid the foundation for cryptocurrencies as productive assets. Much of the DeFi system is underpinned by DAI, a dollar stablecoin issued as a result of CDPs. It’s commonly used across Ethereum applications to denominate trade and serve as collateral.

Examples: MakerDao

Source: Dune Analytics, CoinShares Research (February 2022)

Source: Dune Analytics, CoinShares Research (February 2022)

Collateralised Debt Markets

Just as in decentralised exchanges, lending applications can be two-sided marketplaces where users are either depositing funds [to be lent] or applying to borrow [community-deposited funds].

Rather than CDPs where a new credit asset is created, collateralised debt markets loan existing crypto assets. While still facilitated by a protocol that requires full collateralisation, these loans originate from liquidity providers aiming to capture yield.

Lenders and borrowers are typically matched peer-to-peer or peer-to-pool. Peer-to-peer matching operates similarly to OTC type arrangements where two parties can easily customise their terms, enabling fixed interest rates or specific durations. Alternatively, peer-to-pool loans operate similarly to an AMM. Out of the two, peer-to-pool applications have seen much greater volume compared to peer-to-peer loans in DeFi’s short history.

Peer-to-Peer examples: Dharma

Peer-to-Pool examples: Compound, Aave, Cream

Derivatives

In DeFi, several applications fall under the traditional definition of a derivative—a financial instrument whose value is derived from the value of an underlying asset or benchmark.

Synthetic Assets

Synthetic assets are designed to mimic the performance of an underlying reference price, tied either to a single asset, basket, or index. Some traditional examples of references include stocks, bonds, real estate, precious metals, or crypto assets. However, given the flexibility to reference virtually any measurable feed of data, some less familiar methods include pegging assets to the total value escrowed in a project or the number of downloads for a given app. Synthetic DeFi assets benefit users who want exposure to financial instruments that may be restricted to certain geographies, categories of investor, etc.

To track the performance of its underlying, the applications creating the synthetic assets require special data feeds called oracles, that provide the price, performance or index information from sources outside of the blockchain itself. This means that a predefined entity (or set of entities) is utilised to report data concerning the underlying asset to which a synthetic asset is pegged. Further discussed later on, these external data sources introduce dependencies and degrees of trust in third parties to maintain and properly report the requested data feed(s).

Furthermore, these projects typically require some form of collateral to mint each synthetic token. Which assets are approved as collateral, the collateralisation ratio, and the liquidation levels typically vary between each application?

Examples of synthetic asset platforms include Synthetix, UMA

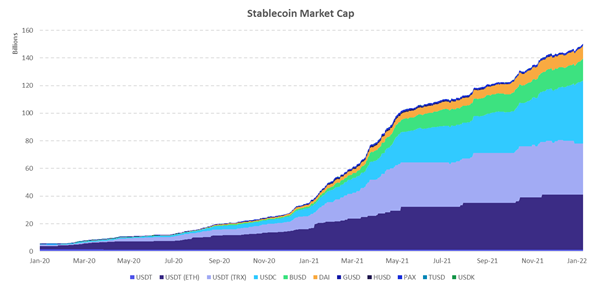

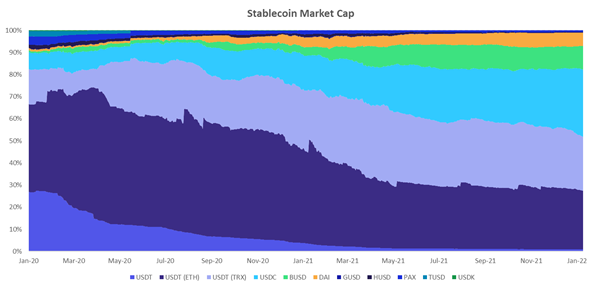

Stablecoins

Stablecoins are a type of synthetic asset that aim to closely mimic the price of an underlying asset or basket. These tokens are worth mentioning separately as they’re typically pegged to fiat currencies (i.e. USD) and accumulate high volumes as a familiar medium of exchange and unit of account.  Source: CoinMetrics, CoinShares Research (February 2022)

Source: CoinMetrics, CoinShares Research (February 2022)

A main benefit of stablecoins is mitigating the price volatility present in cryptocurrency markets. As you may expect, the majority of stablecoins are tied to USD, and the most popular DeFi spot and derivative markets utilise these “crypto-dollars” to denominate trading pairs or settle contracts.

It’s worth mentioning that the topic of stablecoins has immense depth as there are many different types and issuing entities. For example, China (among other countries) has been keen to launch a central bank digital currency (known as a CBDC), the original proposal for Facebook’s Libra project aimed to create an SDR-type basket, and Tether has been releasing crypto dollars since 2014.

Source: CoinMetrics, CoinShares Research (February 2022)

Examples of stablecoins include: USDT, DAI, USDC, TUSD

Futures/Options Contracts

Futures, forwards, options, and swaps are all familiar derivatives in traditional markets. While this area of DeFi is relatively underutilized compared to others, crypto exchanges have started offering the ability to hedge and speculate with these instruments.

The most notable of these trading products is a special type of futures contract called a perpetual contract. Pioneered by the BitMEX exchange. Rather than a traditional futures or swap contract where two parties agree to buy, sell or swap an underlying asset upon or until a predetermined date, perpetual contracts do not come with an expiry. Instead, the contract is permanent where the underlying is never delivered, and traders pay fees to maintain their position.

Examples of non-custodial futures/options exchanges include Hegic, Perpetual Protocol, dYdX, and OPYN.

Event-Based Assets

Event-based tokens are generally issued in prediction markets where observable events have unique tokens that correspond to a range of potential outcomes. Each token is tied to a specific outcome, and the proper result is conferred according to an agreed-upon arbitration source at a predetermined time. As speculators allocate capital to a potential outcome, they are effectively betting on an identifiable result at some point in the future. The ratio of long and short interest determines the payout of the contract, effectively generating a crowd-sourced implied outcome probability.

Once the event has occurred, the agreed-upon source will signal which outcome was correct. At this time, all the crypto assets dedicated to this event will be distributed proportionally to the speculators that invested in the correct outcome.

Example of prediction market: Augur, Gnosis

Insurance

Insurance in DeFi is a way for traders to hedge against technology risk. It’s a way to reduce dependency on audits from a community of developers or firms that may lack credibility.

The most prevalent insurance protocol, Nexus Mutual, is established as a mutual in the UK and enables users to take out coverage on specific Ethereum applications. Essentially, insurance claims are paid at the discretion of certain members who choose to serve as claims assessors. These members serve to look at on-chain transactions and review events through the blockchain as a verifiable data source.

While this isn’t necessarily a popular part of the DeFi ecosystem, it may become increasingly important as the risks of these projects come to fruition. To date, many exploits have already occurred in DeFi applications, most notably bZk (~ $90k) and Yearn Finance (~ $2mm).

Examples: NXM, Armor

Asset Management

Asset management is a way for investors to gain exposure to baskets of assets and various active strategies without having to individually manage their exposure. Within crypto platforms, this practice is typically automated with pre-set rules rather than controlled by custodians and asset managers.

These tokenised funds enable users to target different sectors or employ simple strategies such as auto-rebalancing, arbitrage trading, or yield capture. Strategies maintained by these funds execute as written in code, and may be sourced by a widespread community, select manager(s), or casual laymen. By automating their operations, funds may reduce regulatory and fiduciary pressures as anyone can transparently identify fund activities in code.

When investors allocate capital to an on-chain fund, they receive newly issued tokens in return, each representing an entitlement claim to a portion of the value of the assets owned by the fund.

Examples of on-chain asset management: Set Protocol, Yearn Finance, Enzyme Finance

Major DeFi Opportunities

Efficiency

DeFi transactions are typically triggered without much, if any, manual participation, where software programs take on the role of and approve each step along a transaction's execution process. Automating financial agreements grants the opportunity to not just increase the speed in which transactions are processed, but also reduce their cost. While cryptocurrency networks require fees to settle these agreements, the cost of such fees may be less than paying multiple intermediaries for their services.

Composability

As mentioned earlier, most DeFi projects are protocols that strive to replicate financial services inside of blockchain platforms. Since many of these projects are built upon the same platforms, it allows coordination and engineering of automated financial services involving multiple levels of execution. This dynamic is core to many advocates' theory that DeFi applications are ‘monetary lego blocks’ that can be freely and creatively combined with others, serving as building blocks for a new online economy.

Accessibility

Generally, DeFi applications are open to anyone with access to a connectable wallet. In many cases, this is as simple as having a mobile phone and internet connection.

The lack of identifying information traceable through a wallet greatly reduces the risk of discrimination or censorship. This aspect effectively safeguards equal opportunity across income classes, religion, birthplace, gender, race, etc. In a best-case scenario, DeFi applications could deliver financial services to much of the unbanked population. The World Bank, in a 2017 report, estimated that two-thirds of unbanked adults have mobile phones, a popular and useful device to host a wallet.

Transparency

Typically, DeFi protocols are written as open-source software, meaning the programmed rulesets by which applications operate are open to public scrutiny. Each participating member along with any interested outside parties can transparently audit how each service works ‘under the hood’. Further, these applications typically settle transactions to public blockchain systems (Ethereum, Binance Smart Chain, Solana, etc.), where users can verify which, transactions are processed and finalised. Where much of the digital world is built on ‘black box’ algorithms of major tech companies, DeFi aspires to be a segment where innovation is more transparent and tractable.

Major DeFi Risks

Technology

Built upon blockchain systems designed for flexibility, much of the DeFi sector is the result of creative engineering with relatively new technologies. As a result, users should expect that these applications are unlikely to be bullet proof.

Just as the dependencies across applications introduces technology risk, so does the dependency upon an underlying blockchain system. Given these DeFi services are built within cryptocurrency platforms (such as Ethereum, Binance Smart Chain, Solana, etc.), each transaction submitted to these platforms must undergo a settlement process before being finalised into a blockchain. As a result, any issues that relate to an underlying settlement system will have a negative impact on the DeFi services that typically benefit from such settlement systems. In other words, if the underlying blockchain breaks, so do all the applications riding on it.

This means that users participating in DeFi applications are not just introduced to the technology risk of a particular application, but also to the risk of each application their transaction touches, and to the blockchain platform on which it settles.

Centralisation

While it may seem counterintuitive, applications in the ‘decentralised finance’ sector oftentimes suffer from centralisation risk. Rather than a binary measure, decentralisation is better understood on a spectrum, whereby some applications are decentralised than others.

Most blockchain systems designed for the type of complex financial transactions necessary for DeFi applications do so with persistent and automated contracts. Many underlying blockchain systems are designed such that the contracts within an application may be modified by developers to achieve evolving functionality and/or project goals.

To enable this, DeFi applications often endow admin keys that enable a group of individuals (likely the founding members/developers) to alter parts of the operating code or perform emergency shutoffs. The existence of such keys creates a bit of a double-edged sword, where they may simultaneously be used to fix outstanding vulnerabilities, but also to drain users’ funds. It’s worth noting that many projects have one (or several) keys shared among many stakeholders, where a threshold of participants must cooperate to enact change.

While precautionary techniques such as these may mitigate technology risk, if these keys are identified by malicious actors or aren’t properly stored, there could be catastrophic consequences.

Dependencies

While the dependencies described above are agnostic across all DeFi projects, other dependencies may arise due to specific mechanics of each protocol. This may simply be the use of external data sources (oracles) that determine exchange rates, but also more unsettling methods such as rehypothecated collateral. Nonetheless, the methodology of DeFi projects may introduce unparalleled idiosyncratic risk.

Scams

Most projects within the DeFi sector are open source, meaning they are infinitely and trivially copyable. In some cases, this has led dishonest actors, and specifically dishonest developers, to deceive investors into unstable or insecure investments.

In August 2021, the largest DeFi exploit to date occurred draining $611 mm from cross-chain protocol Poly Network. The protocol was designed to act as a bridge between multiple blockchain networks, and as a result, assets on Ethereum ($273mm), Binance Smart Chain ($253 mm) and Polygon Network ($85 mm) were all affected.

Regulation

The guidelines by which DeFi applications may operate are largely ambiguous in many jurisdictions, meaning that unfavourable laws and compliance mandates may emerge, potentially weakening or permanently shutting down certain projects within the DeFi sector.

While increasing levels of decentralisation within each individual project imparts increasing levels of protection from undesired and unfavourable intervention by authorities, the structures of many DeFi projects (as discussed above) are such that they are realistically quite vulnerable to regulation by a motivated authority.